The Algorithm is Everything

Thinking in systems

I’ve written about systems for years, and I try to incorporate systems thinking into everything I do. It’s a habit I developed back in the 1980s when I studied electrical engineering at Northwestern University. Though everyone interacts with dozens or hundreds of systems every day, most people rarely consider how any of them work. You can’t understand the world without understanding systems at a fundamental level. If you fail to think systemically, you will misinterpret events, fall prey to disinformation, make worse decisions, and your ethics will suffer. Worse, you may focus excessively on personalities or events disconnected from the systems they inhabit.

Systems are nested. The universe is the top level, then galaxies, then star systems. Our planet is one large ecosystem with inputs of infrared radiation from our star, along with occasional meteorites. Civilization runs inside that ecosystem while transforming it. Within civilization are governments, cultures, corporations, cities, religions, civic groups, neighborhoods, homes, shops, automobiles, traffic signals, families, and individuals. All of those rely on banking, manufacturing, distribution, energy and more. Each individual has many subsystems—nervous, circulatory, respiratory, digestive and so on. Within the human body are still more cellular subsystems: energy production, self-replication, intracellular communication, waste disposal. Underpinning our cells is yet another system of elementary particle physics.

Everything is connected. Not in a conspiratorial sense, but through cause and effect. If your body is invaded by viruses or microplastics, that’s the result of thousands of systemic decisions about how to run our civilization, and what rules and laws apply to whom.

Most systems operate outside our awareness and that’s usually fine. We don’t need to think about what our trillions of cells are doing. Breathing is involuntary. We mostly eat when we’re hungry, drink when we’re thirsty and sleep when we’re tired. Normally we shouldn’t have to think too much about human-built systems either, provided they are well designed and self-regulating. Most people send a text or email without understanding any of the processing between them and the recipient. Well-designed systems just work.

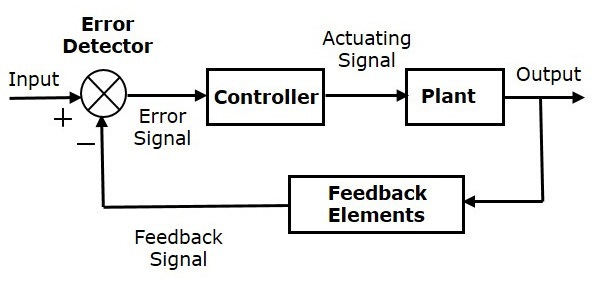

So what composes a well-designed system? To understand this, we’ll have to explore basic control theory. Consider the two main types of systems: open-loop and closed-loop.

Open loop systems are those which run without considering the result. They still have a controller, but it’s unconnected to any measurement of output. Once in motion, that system is out-of-control unless the input changes. Examples include volcanic eruptions, tides, and electromechanical systems like timers. Volcanoes are triggered by magma pressure, and they erupt until the pressure is relieved. Tides rise and fall based on the rotation of the Earth and the orbit of the Moon. Traffic signals on timers operate regardless of fluctuating traffic conditions, which can lead to gridlock. Everyday examples of open-loop systems include a heater without a thermostat, a bathtub without an overflow drain, or a toilet without a float valve. Once you turn on the heat or water, if you don’t monitor that system, you’ll face an unpleasant result. The solution of course, is to create a closed-loop system.

The key to a closed-loop system is the error signal. When there’s an undesired result, we need to measure it and use that information to adjust system function. With a volcanic eruption, there’s no adjustment possible. With a heater lacking a thermostat, there’s no error signal because we’re not measuring temperature.

Practically every modern safety and convenience we take for granted relies on a closed-loop system: Measurement of error, triggering a correction. Smoke alarms alert us to the presence of particulates in the air indicating there may be a fire. Airbag systems measure g-forces and activate on impact. Modern heating and cooling systems monitor temperatures and cycle on and off based on our setpoint. Flush toilets refill to a set level and then stop. Well-designed traffic signals adapt to congestion. Cruise control measures speed and sends the error signal to the throttle to maintain our desired setpoint, even while going up and down hills. But even then, we have to slow down manually when we hit traffic. A further innovation is adaptive cruise control that detects cars in front of us and automatically slows the vehicle down. We simply can’t survive without these well-designed, high functioning systems.

Now that you understand the basics, let’s move on to algorithms. Algorithms are complex nested systems that take in information, process it according to rules, and produce outputs. Examples include: Credit scores, social media feeds, military target selection, and governance.

Credit Scores: A credit scoring algorithm evaluates a person's financial trustworthiness based on inputs like payment history, credit utilization, account age, and recent inquiries. The system applies weighted calculations to these factors, processing them according to proprietary scoring models (e.g., FICO or VantageScore). The output is a numerical score that influences loan approvals, interest rates, and financial opportunities.

Social Media Feeds: Social media algorithms curate content by analyzing inputs such as user engagement (likes, comments, shares), browsing history, and relationships with other users. These inputs are processed using ranking models that prioritize content predicted to maximize user retention and ad revenue. The output is a personalized feed displaying posts, videos, and ads tailored to an individual’s behavior, often reinforcing existing interests and viewpoints.

Military Target Selection: Targeting algorithms in modern warfare integrate inputs such as satellite imagery, intelligence reports, radar data, and real-time battlefield assessments. These inputs are processed through decision models that classify threats based on priority, risk assessment, and legal/moral constraints such as rules of engagement. The output is a ranked list of targets, which may be presented to human operators for final approval or, in some autonomous systems, directly executed through precision-guided munitions.

Democratic Constitutional Governance: A democratic system operates through inputs like citizen votes, public discourse, and institutional checks and balances. Constitutional laws and political frameworks process these inputs, determining policy outcomes based on electoral mechanisms, legislative deliberation, and judicial review. The output is governance in the form of laws, regulations, and leadership selection, ideally reflecting the will of the electorate while maintaining systemic stability.

Needless to say, these algorithms are everything. They are increasingly a matter of life and death for millions—if not billions—of people. They should therefore be open for inspection, and their parameters should be a matter of robust public debate. But increasingly the opposite is true. Only a select few people understand how credit scoring, social media curation, or military target selection work. And our system of democratic governance is becoming more opaque, less accountable and less responsive to citizen feedback.

Algorithmic systems interact with each other. Social media curation has proven its capacity to both swing democratic elections and unleash genocide. A small tweak at Facebook or X or YouTube can alter the information intake of millions of people and have a large impact on sentiment, which in turn can incite murderous hate, elect maniacs who can change laws, and weaken democratic checks and balances. The rule of law is now under algorithmic threat, both from disinformation, and from the massive injection of wealth into the political system. The combination of extreme wealth and opaque algorithms are rendering our civilization increasingly ungovernable.

Many systems we’ve relied on for decades are now having their feedback loops disconnected, turning into open-loop systems that are guaranteed to run amok. When planes crash or fires or pandemics rage or the economy stumbles, those are all preventable system breakdowns. Most people focus only on triggering events like pilot error or air-traffic-control fatigue, or “who started the fire.” Avoid this like the plague! Always try to identify the larger systemic failures. Because that’s the only way anyone can truly understand what happened, and prevent future disasters. If we don’t fix systems, then effectively disasters become planned events. I’ll be discussing how to spot systemic risks in a lot more detail in this publication going forward. The more you can apply systems thinking to the ongoing chaos of our new administration, the more you’ll understand what they’re up to, and consider how we might be able to slow or repair the damage.

Every member of democratic societies has to read that!